Eye of the Child

by

William Ayot

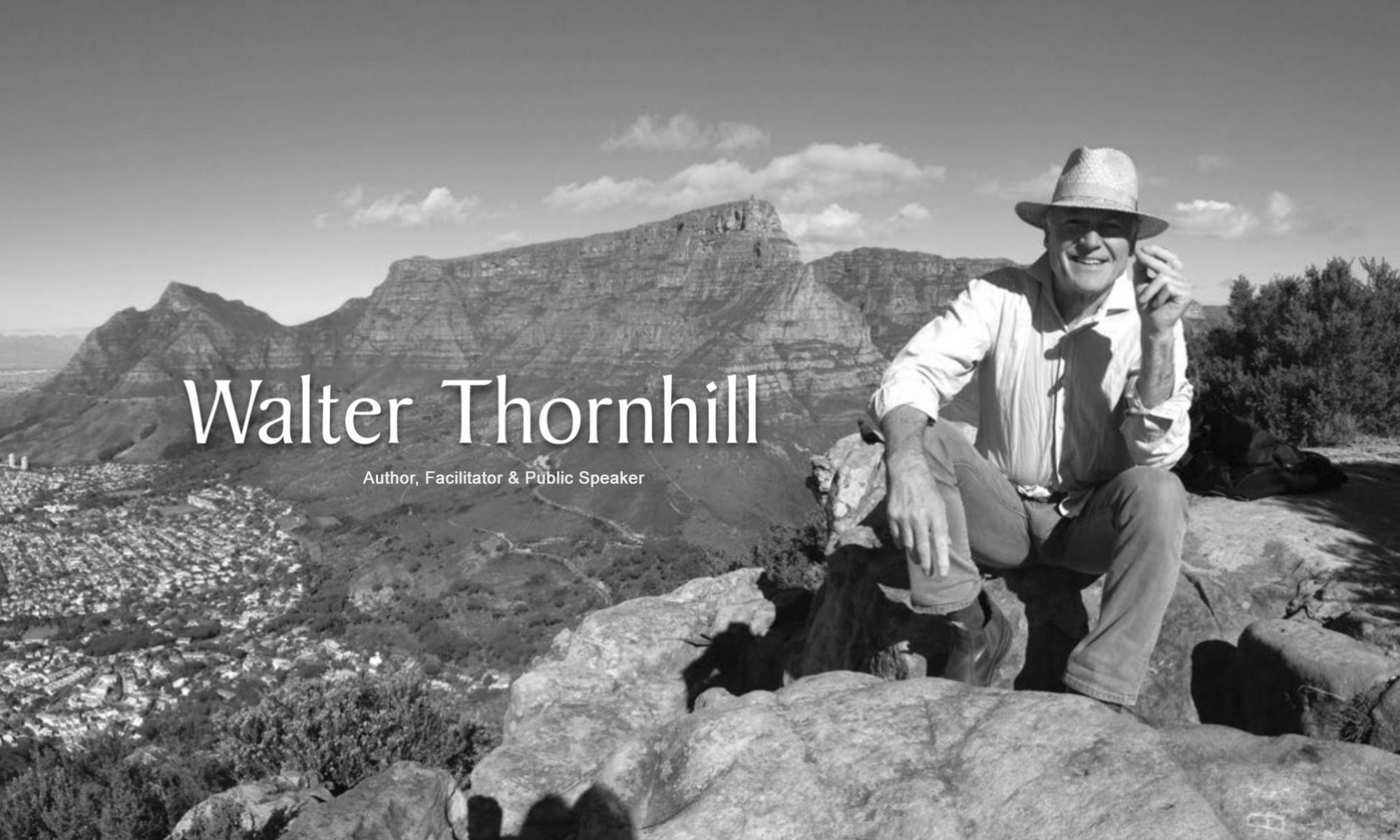

On the surface, this is the memoir of a successful banker, business consultant and corporate finance director, the kind of prosperous insider you might meet at a London cocktail party, or week-end country house party. More than that, it is the story of a sportsman, someone who knows the loneliness of endurance training, the reality of breaking through the cyclist’s wall of pain, and the elation of bursting from the pack to win the stage in that final, wild sprint for the line. Most importantly it is the tale of a lost and often neglected little boy, shunted from pillar to post and hurt in ways that no youngster should be hurt. This is a tale of survival.

I first met Walter Thornhill through what was rather grandly called the men’s movement, a random gathering of teachers, poets, shamans and everyday men who met at workshops and conferences, back in the nineteen nineties, to explore the deeper issues of masculinity. By delving into the underworld of myths and wonder tales, we were able to explore our naivety, our shadowy behaviours, and our emotional incompetence. By talking-out the pain that lays beneath the surface in most men’s lives, we found ourselves cleansing the often-overlooked, and rarely-healed wounding that is the male lot.

Over the years Walter and I kept in touch, in that desultory way that men do when they have profound experiences and unfinished business in common. We would talk through the odd local difficulty or share our occasional ups and downs, doing each other favours as we could and generally maintaining a kind of friendship through a sense of fellow-feeling and a typically male distance. It was therefore no surprise, after writing and publishing my own story of survival, denial and growth, to discover that Walter was doing much the same sort of thing over the same period of time.

Walter Thornhill is an adult child. That is to say, he is a fully-grown survivor of alcoholic parenting. Growing up with a father, and particularly with a mother who drank to excess, he had visited upon him many of the hurts and traumas experienced by any boy or girl when the primary focus of a parent’s life is the bottle and not their child. While he never resorts to such an easy label, his book is infused with the bewilderment, shock and inescapable diminishment of the adult child. It is also filled with the self-determination and tenacity of the child who seeks out love wherever he can find it; who finds a place of belonging when no such thing is on offer at home. This book is a testament to Walter Thornhill’s resolve to travel beyond mere witness and return with the gold of healing and understanding.

As an adult child myself, and a frequent flyer down the routes that he travels in this book, I was profoundly moved by young Walter’s loyalty to his mother and yearning for his absent father. I was also touched by his bafflement, his constant ability to bounce back, and his life-preserving ability to dip into and out of denial. Truth in alcoholic homes is known to be a delicate and perishable thing, often bent out of shape by drunken cruelties and the shame of waking to the carnage of the night before. What we often overlook in such circumstances, is the need we have as children to maintain the fiction that all is well and that our carers – no matter how lost – remain reliable sources of solidity and safety. Following Walter’s slow dawning around his mother’s helpless slide into alcoholic viciousness brought it home to me, once again, how the growing human mind has the most extraordinary ability to unpick its denial systems as the ability to ‘handle the truth’ develops with age.

To survive in such difficult formative circumstances, one needs more than the random kindness and generosity of ‘onlookers’ caught so well in the pages of this book; one needs a focus and a passion, a kind of saving obsession. The great mythologist and men’s work leader Michael Meade, once said that to thrive in the wide world, a boy needs a cosmology and a skill. In Walter’s case, he found his skill, which he terms his ‘anchor’, in sport, specifically in road and track cycling. We follow his development from schoolboy tyro to Springbok status, to representing his country, and becoming a sporting celebrity in his chosen field.

Like many of their alcoholic parents, adult children are invariably both sensitive and gifted. The discovery and development of their gift – and the necessary drive that accompanies it – is what can turn a shambolic start in life, into concrete achievement and ultimately self-realisation. Walter’s cycling career is just such a triumph. Having come from a similar background, where encouragement and support were rarely given in the home, I was right there with Walter, at the road side in Mozambique as the peloton pelted through, cheering him on as he found meaning and self-respect on the track, and finally applauding as he crossed the finishing line, a fully-fledged champion – and alive.

As for a cosmology – by which I mean a map of our surroundings, their cultural history, mythic topography, and belief systems – Eye of the Child is set in the polyglot, many cultured suburbs of South Africa from the nineteen fifties through to the sixties and seventies. In suburbs and villages with reassuringly English names, we meet a broad mix of Afrikaner, Dutch, and Greek friends and family members, their distinctive voices and stories weaving into and around Walter’s own as he moves from school to school and neighbourhood to neighbourhood. Furthermore, the whole is played out before the vast rotting edifice of the already crumbling apartheid system, with its atrocities, betrayals, cruelties and petty indignities. Piquant stories of friends and family are added into the mix, balancing the hidden and traumatic events of suburban family life with the ever-expanding trauma of post-colonial South Africa. Thus, the traumas of hearth and home are paralleled by the ever-present, and equally worsening viciousness of the apartheid regime.

A journey through shame then, and humiliation – private, public, cultural and personal. We follow Walter as he grows and learns – arriving at the thresholds of manhood, military service and marriage only part-formed and yet fully independent; naïve in many ways yet street-wise and savvy; full of hope yet depressive and despairing – the eternal paradox of the adult child.

It’s important to say that this is not a ‘victim book’. It takes pains to point out the vulnerabilities and ‘backstories’ of all the major players, as well as the other kids and adults that surrounded, and inevitably influenced, the life-hungry and observant young Walter. We don’t get the endless litany of accusations and self-justifications we might expect in such a book. We find a tightly observed and often amusingly detailed accretion of experiences, the laying-down of a life, and the alternate, sediment-like seams of wounding and hidden potential that go into the making of a man. We also find that it is written with a great deal of love.

A word of warning. Don’t read this book if you are looking for a well-wrought treatise on the incidence of alcoholism in middle-class white families in post-colonial Cape Town, or a literary masterpiece about the history of cycling in South Africa. This is neither an academic text, a sporting history of the sixties and seventies, nor a platitudinous new age self-help book. It is infinitely more urgent, more raw, and more demanding than that. In fact, Walter Thornhill’s words and images tumble out in such a stream-of-consciousness rush that (despite a clear explanation for this in the text) a reader can find themselves momentarily disorientated or confused by both the use of language and the intensity of Walter’s need to tell. This is a deliberate choice on the author’s part, a way of dropping us into the perplexities, upheavals and gradual clearings of his path. It’s well-worth staying with this, as the raw unfiltered nature of the telling adds to the depth and quality of the read. All in all, this rousing and engaging book bears all the authentic hallmarks of one man’s unique and often fascinating experience, delivered in the first full rush of heartfelt and occasionally visceral recall. I hope you enjoy the ride!

William Ayot

Author of “Re-enchanting the Forest:

Meaningful Ritual in a Secular World”

Vinalhaven, Maine.

August 2017